This article is part of our Focus on India Series through which we share our findings from our recent research in India. Our studies lead us to believe India to be the most complex and promising market for Digital Money in the world. Our Digital Money in India 2014 Viewport was published this week, to reflect our latest findings. In this post, I highlight a few of my own thoughts from my visit to India and my assistance in preparing the report.

Going online in a labour-rich environment

India is the second most populous nation on Earth, but unlike many other large nations it still has a strong population growth rate. Finding work for such a large and growing population has led to a rather unique model of business in India. The labour intensity of almost any form of business in India is considerable compared to economies of the West. The degree to which this reflects on financial services as they go digital was one of the most noteworthy findings from our market visits to India in 2014.

The combination of relatively low labour costs and the desire to deliver a highly personal service has led to a distinctive form of labour intensive business practices in India. A good example of can be found in the ‘cash on delivery’ model offered by the online retailer FlipKart. This model allows FlipKart to serve consumers who do not have access to payment cards or other online payment methods. This allows buyers to change their minds after physically inspecting the goods rather than simply trusting the supplier. These features are extremely attractive in an economy that lacks widespread participation in the banking system and that is yet to completely trust online retailers. On the other hand, FlipKart must contend with the drawbacks of this scheme, in the form of high labour costs, in order to deliver goods and collect payment and incurs the risk that some buyers will refuse to accept and pay for goods once the initial impulse that motivated their purchase has faded.

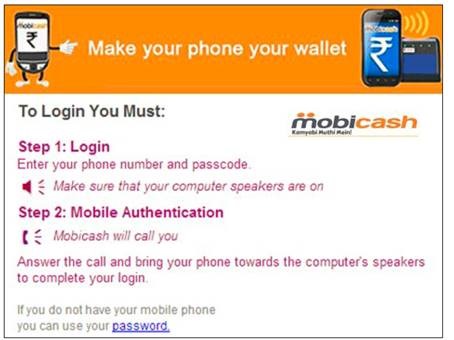

Another good example of labour intensity is that of MobiCash India. They use a phone call to an operator as part of their login process as shown in the figure below.

It is not a unique feature of India that high employment by a firm leads to better relations with both the public and the government, but it is nonetheless a strong motivator for businesses to employ more people than they might otherwise choose to. Finding productive work for these employees has led to many of the models of business we see today.

The consequence of this for firms entering the Indian market is that they have access to an entirely new degree of freedom, since the availability and cost of labour is so low. This can be a great advantage if done correctly, but it may pose a problem for many Western firms. These firms have spent decades attempting to reduce the labour intensity of their operations, and finding innovative new ways of increasing employment while still making a larger profit may be difficult given their traditional mind-set.

Digital Money in the fight against corruption

The other feature of doing business in India that I would like to highlight is the continuing struggle against corruption. India is currently the 94th most corrupt nation on Earth. The growing middle classes and the freedom of the press in recent years has fortunately brought corruption more and more under the spotlight, and politically the reduction of corruption is high on the agenda of the Modi government.

Nevertheless, corrupt and rent-seeking behaviour is still rife in the country compared to many other major economies. The relationship between corruption and digital money is an interesting one. By using digital money methods such as online payment, mobile payment and cards, transactions become visible to the wider economy. This runs contrary to the cash-based ‘dark’ economy that corrupt and criminal elements prefer. When transactions go unrecorded, it is much easier to evade taxation or arrest.

Consequently, transforming the economy into one that is predominantly non-cash could improve governance by making corruption and criminal money transfers more visible and easier to punish. Recent progress towards a non-cash economy in India has been good. A noteworthy effort is the Pradhan Mantri Jan Dhan Yojana (PJMDY), which resulted in the addition of over 53 million new accounts by end September 2014.

We saw unique services that now cross online, mobile and offline environments. But the distinct “Assisted Model” of service through which services are developing seemed to us to be a double-edged sword. On the one hand it has the potential to build more secure and convenient services and guide consumers in using these for the first time. On the other hand, these human checkpoints could potentially be subverted if certain risks are not anticipated from the very start.

Looking ahead

The move away from cash holds a great deal of promise for India’s future. At the same time it is important that the new systems put in place in countries such as India are architected to be resilient against any possibility of the emergence of a parallel, informal digital economy. Such developments would subvert the existing achievements in digital money. The bullying practices of the past that result in corruption or criminal activity could be replicated in the new digital world if sufficient safeguards are not put in place. Digital transactions must also be encouraged to become an everyday part of people’s lives. People who get access to the new mobile-enable bank accounts must have a reason to use the money online, rather than cashing their receipts and allowing accounts to go dormant.

This combination of responsible oversight and public interaction will make it harder to conceal illicit activities. There may also be a backlash against the spread of digital money in India by corrupt or criminal elements. These will not be the only objectors to the changes that moving towards a digital money economy will attract, but due to their powerful positions in the current economy, these elements may be better placed to disrupt the activities of businesses and users, especially in isolated or rural areas.

In summary, firms looking to enter the digital money market in India face a unique business environment, in which labour is cheap but high employment is necessary and where digital money is in demand but could find itself in conflict with powerful opponents. The promise of India lies in its vast and growing population, but accessing this market will require inventive solutions to inimitably Indian problems.

We invite you to join us in our campaign to celebrate India’s progress in going non-cash. To learn more, register on our portal or just drop us a line at contact@shiftthought.com.

Chief Analyst, Digital Money

Co-author of The Digital Money Game, Author of Virtual Currencies – From Secrecy to Safety

Join us to explore ideas at The Digital Money Group on LinkedIn