In the context of the dramatic price changes faced by Bitcoin in recent weeks, Dr. Neeraj Oak explains why it isn’t all bad news for the supporters of virtual currencies.

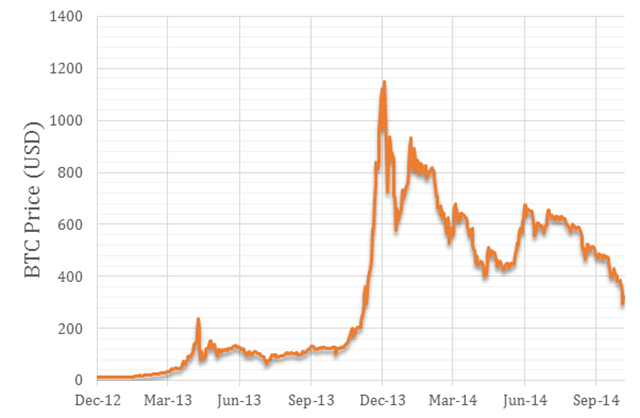

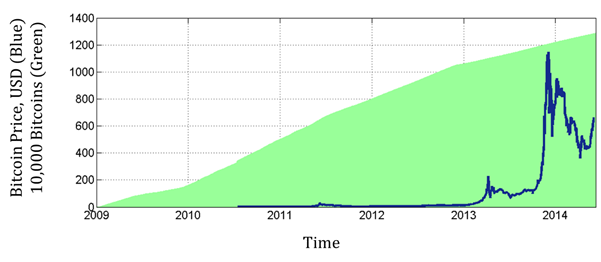

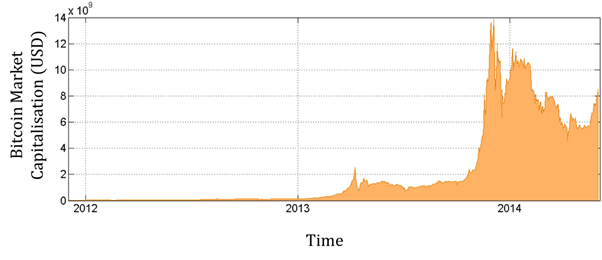

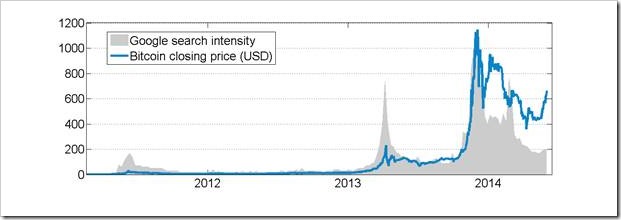

With the price of Bitcoin continuing to fall from the dizzying peak of over $1100 in December 2013 to a current value of around $300, it is easy to assume that this is a very bad thing for the virtual currency community. In reality, it might actually be a blessing in disguise. Here are three reasons why:

Reason #1: High prices dissuade new users

The operating model of any virtual currency is to grow its user base to become as widely accepted as possible. However, if the price of the currency is too high, this can become a psychological barrier to new adopters, who may feel that they do not get a good deal when they exchange fiat money for Bitcoin. This is especially true when one considers that the price of Bitcoin in September 2014 was around 100 times greater than its price in January 2012. New users may find it unsatisfying to pay such a high price for a commodity that was so recently considerably cheaper.

A lower price for Bitcoin is helpful in this respect, but what is even more important is that the price becomes stable. This does not mean a stagnant price, but rather one that has a relatively predictable trend. Volatility and uncertainty are not attractive features for new adopters.

Figure 1: Bitcoin prices (USD) since December 2012

Reason #2: Reducing the dominance of Bitcoin encourages the growth of newer virtual currencies

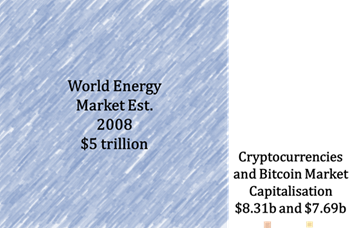

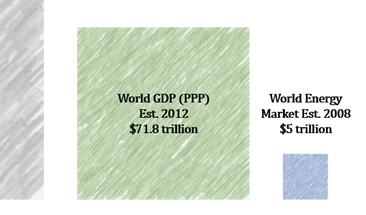

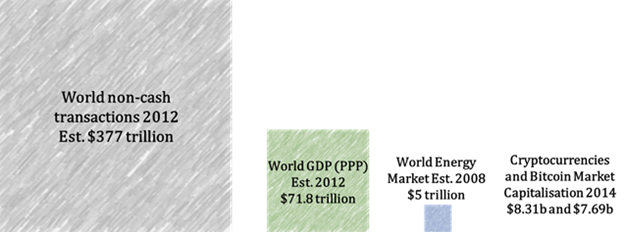

The price of Bitcoin towers above all the major alternative virtual currencies in the market today. A high price often brings the added advantage of greater visibility and prestige for the currency, making potential investors and adopters sit up and take notice. One of the problems of the dominance of Bitcoin is that many of the newer, smaller virtual currencies have struggled to find the limelight. With the price of Bitcoin falling, opportunities may appear for these currencies to garner more attention. Ultimately, this is beneficial for the virtual currency community; these alternative virtual currencies tend to be at the forefront of innovation in the field, and increasing their profile will help to spread ideas that could improve the prospects of all virtual currencies.

Reason #3: Deflation encourages speculation

Throughout the meteoric rise of Bitcoin stories have spread of the enormous fortunes made by early adopters. So long as the price of Bitcoin continued to increase, the idea that such price rises were somehow systemic became almost credible. When investors believe that the price of a commodity is bound to rise, they will often pay over the odds to acquire it, raising the price further. On the other hand, people using Bitcoin as a transaction method would be at a disadvantage, since the prices of goods and services that can be bought using Bitcoin often lag behind the headline Bitcoin price.

The result of sustained increases in Bitcoin prices is that it becomes a speculative vehicle rather than a transaction vehicle. This crowds out the true value makers in the currency: the consumers and merchants. Without these two groups of Bitcoin users, it is hard to conceive of a sustainable business model for Bitcoin- it would merely be a speculative bubble.

The recent fall in Bitcoin prices will do a lot to dispel the myth that short-term investments in Bitcoin are bound to pay off because it is a deflationary currency. With luck, this will help to drive away the types of speculators who drive the notorious volatility of Bitcoin prices.

To summarise, the recent fall in Bitcoin prices may have been painful for many of its users, but may help to create a healthier, more sustainable virtual currency. The Altcoin community too should take note; this could be their chance to assume the leadership position in the rapidly changing virtual currency domain.

Dr. Neeraj Oak, Chief Analyst, Shift Thought

Author of Virtual Currencies – From Secrecy to Safety, co-author The Digital Money Game